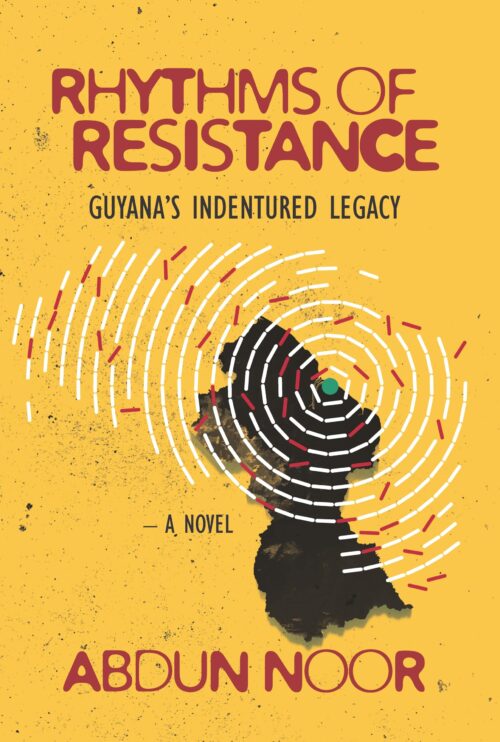

Set in tumultuous 1960s Guyana – a nation on the cusp of independence – the novel unfolds amid rising nationalist fervour as leaders like Cheddi and Janet Jagan and Forbes Burnham come to power. The novel Rhythms of Resistance: Guyana Indentured Legacy is a book that is difficult to forget. It is fiction, but a well-crafted one; a work by Dr Abdun Noor that is a poignant reflection on a painful past that has shaped entire Caribbean societies. The book bridges the gap between personal memory and political transformation, exploring the traumas of indenture and the promise of a new generation, set mainly in Guyana during the 1960s. The novel, using the example of the Majeed family, particularly the young and insightful Reeta, provides a heartfelt account of how generations of silence, trauma, and resilience are passed on.

The book begins in a very tender and disturbed tone. Noor allows the reader to walk into the story not through dramatic incidents, but through ordinary life in a village where feelings are usually concealed, and reality is not to be spoken. At the centre of the story is Reeta: brilliant, bold, and pining to know more about her family. However, her journey to uncover her family’s past reflects Guyana’s broader journey in search of identity and a new future beyond colonial rule. Her inquiries disturb her father Mohon Singh, who bears the burden of history on his body and mind. It is in the shadow of Guyana’s indentured history, which lies hidden beneath the background of Mohon Singh, that the family of Majeed is curbed. This figurative shadow can be interpreted as the period of indenture (18381917), where hundreds of thousands of Indian workers were imported to the colony. He is the person who provides Noor with the chance to revive the complex legacy of Indian indentured workers who had been brought to British Guiana by false promises and poor working conditions.

What makes the novel powerful is that Noor does not treat indenture as a distant history; instead, it is a living reality. Historically, between 1838 and 1917, more than 230,000 Indian indentured labourers came to British Guiana; their descendants constitute the majority of the Indo-Guyanese population, and their cultural legacy and narratives (the rhythms of resistance that give the novel its name) still dominate the country. Instead, he shows how its aftershocks continue to shape families long after the system officially ended. Mohon Singh’s silence is not merely personal—it is the silence of thousands of men who survived plantation labour, racial violence, humiliation, and cultural uprooting. Reeta’s longing to understand her father’s past becomes a larger metaphor for a community trying to reclaim its story. In fact, authors observe that these Indian immigrants left a lasting cultural mark on Guyana; their music, festivals, and customs continued to be living strands of resistance in Guyana’s identity and comprised the novel’s living rhythms of resistance.

While the theme of silence runs throughout the book, Noor also brings strong elements of resistance. The title Rhythms of Resistance reflects the steady, persistent ways in which ordinary people fought back—sometimes through open defiance, sometimes through small, everyday acts of dignity. Resistance appears not only in political movements, but also in the courage of women, in the persistence of memory, and in the refusal to let trauma define the future. This duality of silence and resistance makes the novel emotionally rich. Noor does not present trauma for effect; instead, he treats it with respect, illustrating how communities develop strategies to cope and survive. The relationship between Reeta and her father becomes the space where this history is explored most intimately. Their conversations —or the lack thereof —reveal the painful gap between generations—one trying hard to forget, the other desperate to remember.

The novel is firmly rooted in the political atmosphere of Guyana in the 1960s. Images of personalities such as Dr Cheddi Jagan, Janet Jagan, and Forbes Burnham do not portray them as heroes or villains, but rather as powerful forces in shaping the nation’s imagination. Noor is sparing with them, combining factual accuracy and narrative delicacy. The fact that they are there serves as a reminder to the reader that the personal lives of families, such as the Majeeds, cannot be separated from the broader narrative of Guyana’s fight for independence, its racial struggles, its political disintegration, and its hopes for a more egalitarian society.

The speeches of Cheddi Jagan, the emotional climate of people’s gatherings, and the frictions between Afro-Guyanese and Indo-Guyanese people create a significant backdrop. Noor does not make these political tensions into binaries. He instead demonstrates their richness, such that colonialism created rifts that affected political and community affiliations, as well as familial identities.

Noor has one of the best stories in the novel, and this has been a strong part of the novel. His words are direct and lyrical. Scenes are shown in slow motion, reminiscent of memories. The rhythm reflects the novel’s themes: silent moments, half-finished discussions, and gentle suggestions of wounds that do not truly heal. The language is also attentive to minute details: the sound of cane fields, the rhythms of village life, the aroma of food, and the rhythms of Guyanese Creole and Bhojpuri. These facts bring the Indo-Caribbean world to life without relying on stereotypes or nostalgia.

Noor is written in a non-linear format, where the narrative switches between the past and the present. In a few chapters, the author returns to Mohon Singh’s youth in British India, exploring the frustrations he endured at a young age, the circumstances that drove him to indenture, and the emotional traumas he brought with him to the Caribbean. One of the most striking aspects of the book is the inclusion of these flashbacks. They demonstrate how the violence of the recruitment to the colony, poverty, caste humiliation, police repression, and false promises determined the fate of thousands of Indians who found themselves on the plantations abroad.

The chapters set on plantation estates are compelling. Noor captures the cruelty of overseers, the long hours under the sun, the resistance among labourers, and the fragile friendships that helped people survive. There is a tenderness in the way he describes community bonds—shared food, shared songs, shared suffering. These glimpses into Mohon Singh’s youth explain why he becomes a quiet man. His silence is not emptiness; it is full of memories that are too heavy to speak.

Reeta, on the other hand, is full of life. She represents a new generation—not burdened by plantation labour but shaped indirectly by its consequences. Her desire for education, her political awareness, and her emotional sensitivity makes her a compelling protagonist. She asks questions that earlier generations avoided. Her bond with her father is beautifully written—tender, frustrating, and deeply human.

The supporting characters bring additional layers to the story. Reeta’s mother appears as a symbol of strength hidden behind routine. Her quiet endurance mirrors the often-invisible labour of Indo-Caribbean women. Neighbors, friends, local activists, and political supporters weave in and out of the narrative, creating a believable and grounded world.

The novel’s emotional weight builds steadily. Noor does not rush revelations. Instead, he allows both the reader and characters to uncover the truth behind Mohon Singh’s silence slowly. The moment when fragments of his past come together is profoundly moving. It forces both Reeta and the reader to confront the cost of colonial histories that were never recorded, never archived, but carried painfully within families.

As a reader, I found the book’s emotional honesty its greatest strength. It is rare to see a novel that explores indenture not as an academic subject, but as a living memory that shapes identity, belonging, and personal relationships. Noor’s writing demonstrates how trauma can be passed down across generations—not only through stories, but also through silence, behaviour, and emotional patterns.

The book also speaks powerfully to diaspora readers, especially those whose ancestors migrated under colonial rule. The longing for roots, the confusion about identity, and the desire to understand ancestral histories are universal feelings among diaspora communities. Noor handles these emotions gently, allowing readers to see themselves in Reeta’s curiosity and in Mohon’s inner conflict.

If there is any critique, it is only that some secondary characters could have been explored more deeply. A few subplots—such as the evolving tensions in urban Georgetown or the personal aspirations of other youth in the village—could have received more space. But these are minor issues in an otherwise rich and layered novel.

The final chapters of the book are memorable and satisfying. Noor brings the family narrative and national history together, showing how individual courage contributes to larger political and cultural resistance. The closing lines remind readers that healing begins not by erasing the past, but by acknowledging it.

Rhythms of Resistance is an essential work in Indo-Caribbean literature. It is a blend of the close-knit family narrations and the broad spectrum of political history. Noor is a writer who shares his grief, pain, and great respect for the people whose stories he narrates. He challenges the reader to hear- to the silence, to the hardships, to the rhythms that sustained a people in the middle of a high degree of suffering.

In the end, the novel asks a question that stays with you:

Will you inherit the silence, or will you become the voice of change?

This is a book that honours the past while inspiring the present. It is worth reading, debating, and recalling as an illuminating account of a history easily forgotten. This concludes the review by restating its key points. I recommend this novel to those interested in family sagas and the history of the Caribbean.

Leave a Reply