A Film Review for Pravasi Setu Foundation

Introduction: The Transnational Subject Returns

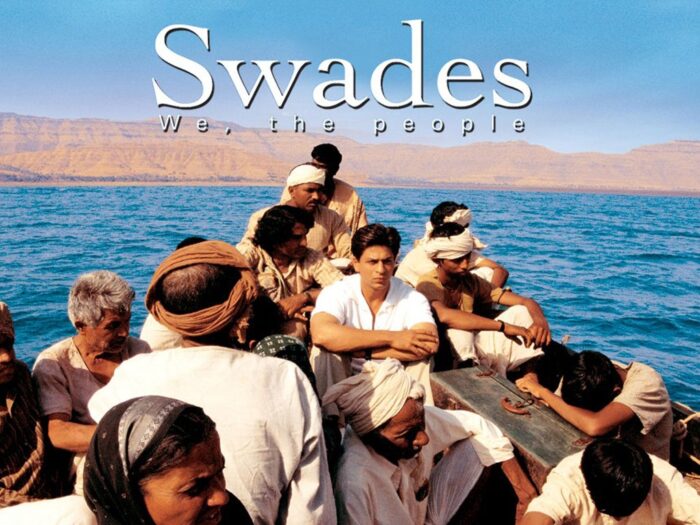

Ashutosh Gowariker’s Swades (2004) presents a counter-narrative to the typical Bollywood treatment of non-resident Indians (NRIs). Rather than celebrating material success abroad, the film engages critically with questions of obligation, belonging, and the ethics of skilled migration. The protagonist, Mohan Bhargava (Shah Rukh Khan), a NASA scientist, returns to his ancestral village of Charanpur to bring his childhood caregiver, Kaveri Amma, back to the United States. This journey becomes a catalyst for examining the structural inequalities that persist in rural India and the moral responsibilities of the transnational subject.

Cultural Dissonance and Performative Identity

The film opens with a nuanced portrayal of cultural negotiation. Mohan conceals his cigarettes with Gita’s assistance to avoid embarrassing Kaveri Amma—a gesture that encapsulates the intergenerational and transnational tensions at the heart of diaspora experience. This moment illustrates how Indian familial structures perceive behaviors such as smoking or alcohol consumption not merely as individual choices but as reflections upon collective family honor. The diasporic subject must constantly navigate between adopted Western liberal individualism and inherited South Asian communitarian values.

This performativity extends throughout Mohan’s village sojourn, where he must continuously renegotiate his identity—neither fully American nor wholly Indian, occupying what Homi Bhabha terms the “third space” of cultural hybridity.

Structural Violence and the Panchayat System

The panchayat meeting sequence serves as a microcosm of India’s developmental challenges. The discussion of electricity shortage reveals how bureaucratic structures deflect accountability by blaming villagers for “electricity theft” rather than addressing infrastructural inadequacies. This scene exemplifies what Johan Galtung defines as “structural violence”—systemic barriers that prevent marginalized communities from meeting basic needs.

The education debate within the panchayat exposes the intersectionality of caste and access to resources. Gita, the village schoolteacher, faces an ultimatum: increase student enrollment within three months or face transfer to an even smaller, more remote school. This bureaucratic pressure reveals the state’s punitive approach to rural education rather than addressing root causes of low enrollment—poverty, child marriage, and caste-based discrimination.

The villagers’ reliance on traditional weather prediction over technological forecasting demonstrates the epistemological divide between indigenous knowledge systems and modern scientific rationality—a tension that Mohan, as a scientist, must learn to respect rather than dismiss.

Caste, Education, and Social Reproduction

The confrontation over school consolidation unveils deep caste fissures within the village. The insistence that children of different castes cannot study together demonstrates how caste operates as both ideology and material practice, reproducing social hierarchies across generations. The devaluation of girls’ education compounds these inequalities, creating what scholars term “intersectional marginalization.”

While urban migration has provided escape routes for some lower-caste families whose children now attend city schools, this has inadvertently created a new problem: rural educational infrastructure remains underdeveloped, serving only those unable to leave. The film thus captures the uneven geography of social mobility in contemporary India, where caste and class intersect with spatial location to determine life chances.

Philosophical Confrontations: Two Visions of Patriotism

The ideological clash between Mohan and Gita represents competing paradigms of national engagement. Mohan, shaped by distance and diaspora, articulates a critical perspective on governmental failures across multiple indicators of development. Gita counters with an ethic of collective responsibility: “We are all part of this nation. We should find solutions rather than merely cataloging problems.”

This exchange reflects a fundamental tension in diaspora studies: does physical distance grant moral authority to critique, or does it disqualify one from speaking about national issues? Can the expatriate who has benefited from Western education and employment legitimately criticize the homeland without being implicated in its abandonment?

Gita introduces the term “Non-Returning Indians” to describe NRIs, a linguistic inversion that cuts to the heart of diaspora guilt. For those who remain, the departure of educated, skilled individuals represents not opportunity but betrayal—brain drain as a form of desertion.

The “Yeh Tara Woh Tara” Sequence: Musical Suturing of Difference

The song “Yeh Tara Woh Tara” following the caste-based education conflict performs crucial ideological work. Through its imagery of stars—each distinct yet part of a unified cosmos—the song articulates Mohan’s vision of unity within diversity. The metaphor of stars suggests that different castes can maintain their distinctiveness while contributing to a harmonious whole, treating all as equal under the same sky. This musical interlude attempts the suturing that social institutions have failed to achieve, imagining national unity while acknowledging persistent fractures. The song performs what politics cannot: a vision of equality that transcends entrenched hierarchies, uniting all the castes in a moment of collective belonging.

The Economics of Marginalization: Haridas and Internal Migration

Mohan’s visit to collect rent from Haridas exposes the catastrophic consequences of caste-based occupational rigidity. Haridas, boycotted by villagers for changing his hereditary occupation, embodies the double bind of caste: remain in your prescribed role and face poverty, or transgress caste boundaries and face social death.

His situation also illustrates rural-to-urban migration under conditions of extreme vulnerability. Those who migrate are not always the aspirational middle classes but the desperately poor, fleeing one form of violence only to encounter urban precarity. This sequence provides a crucial counterpoint to celebratory narratives of migration as upward mobility.

For Mohan, witnessing Haridas’s suffering becomes a pivotal moment of consciousness. The journey that began as a mission of retrieval transforms into an awakening to structural injustice.

The Electrification Project: Development and Agency

The village debate about India’s poverty versus America’s development crystallizes competing nationalist narratives. Villagers defensively invoke “culture and tradition” as compensatory pride in the face of material deprivation. Mohan’s response—”I don’t believe India is the greatest nation, but we have capability”—rejects both cultural essentialism and defeatism.

His statement, “We should do for ourselves rather than adapt to the situation,” articulates a philosophy of collective agency that moves beyond both nationalist rhetoric and passive victimhood. The hydroelectric project he initiates with villagers and his own investment becomes a material manifestation of this philosophy.

The initial failure of the project and Mohan’s problem-solving—discovering the water blockage and releasing it—serves as a metaphor for development itself: obstacles are often mundane and technical rather than insurmountable, requiring persistence rather than genius.

The Impossibility of Return: Generational Divides

Kaveri Amma’s refusal to accompany Mohan to America represents a profound commentary on aging, belonging, and the limits of transnational family arrangements. Her acknowledgment that she cannot adapt to a foreign lifestyle reflects the experiences of countless elderly parents who remain in India while their children settle abroad. The environment one has inhabited for a lifetime becomes not merely familiar but constitutive of identity itself.

Her tears reveal the tragic dimension of diaspora: the recognition that this separation may be permanent, that she may not see Mohan again. The asymmetry of global mobility means that while Mohan can travel freely between continents, Kaveri Amma remains spatially and culturally fixed.

Gita’s Gift: Material Memory and Anticipated Return

Gita’s parting gift of village essentials to Mohan serves as what anthropologists call “objects of memory”—material culture designed to maintain connection across distance. These items are meant to remind Mohan of his origins and, crucially, to foreshadow an eventual return. Her prayers that he will stop before leaving remain unanswered in the moment, but the objects she gives him perform their work later.

The NASA Epiphany: “Swades Hai Tera”

At NASA, Mohan experiences what we might call “productive displacement”—the way distance can paradoxically intensify connection to home. The song “Swades Hai Tera” underscores this irony: only from the vantage point of America can Mohan fully comprehend what India means to him. Every moment at NASA triggers memories of the village, creating an affective dissonance that ultimately becomes unbearable.

His decision to return represents the film’s most radical gesture. The metaphor “Why should the lamp of one’s own threshold illuminate another’s doorstep?” articulates a moral economy of knowledge and labor. If Mohan’s education was funded by Indian resources (directly or indirectly), does he not owe a debt to the nation?

The Myth of Return and the Reality of Non-Return

The conclusion acknowledges its own exceptionalism. While Mohan Bhargava returns, the reality is that most migrants do not. The countless unnamed Mohans—the Raghavs, Anils, Amits, Shahbazs, Jagmanjots, Prakashs—represent the statistical reality of permanent migration. These are not abstract demographic flows but real individuals, each embodying unfulfilled family expectations of return, each carrying the weight of separation across continents.

The film’s 2004 release date is significant. This was before the telecommunications revolution and the dramatic reduction in air travel costs that have since enabled circular migration and sustained transnational connections. In 2004, migration was more likely to be permanent, return more difficult to imagine. The infrastructural limitations of that era intensified the tragedy of separation.

Thus, Swades functions simultaneously as aspiration and elegy—celebrating the possibility of return while mourning its rarity.

Conclusion: The Diasporic Condition

Swades remains one of Indian cinema’s most sophisticated engagements with diaspora and migration. It refuses easy nationalism while taking seriously the claims of collective belonging. It acknowledges structural injustice without dissolving individual agency. It recognizes the complexity of return without romanticizing either departure or homecoming.

For Pravasi Setu Foundation’s mission to foreground diasporic and migration issues, Swades offers a rich text for examining the ethical, emotional, and material dimensions of transnational life. The film asks uncomfortable questions: What do migrants owe to the places they leave? Can one serve the nation from abroad, or is physical presence essential? How do we measure the value of different forms of contribution?

These questions remain urgent twenty years after the film’s release. As global migration accelerates and diaspora communities grow, Swades provides a framework for thinking through the obligations and possibilities of transnational citizenship. Its greatest achievement may be refusing to resolve these tensions, instead holding them in productive suspension—much like the diasporic condition itself.

Also Read here:

Leave a Reply