Overview of Malaysian Society

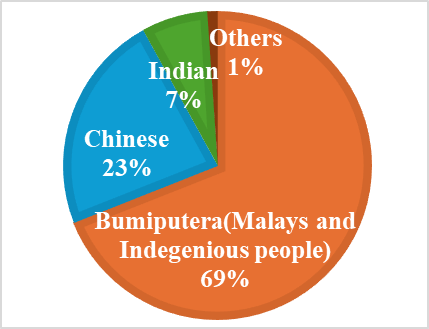

Many Indian immigrants have naturalized in Malaysia. Most of them are Tamil Hindus who migrated from South India as labourers during the British colonial period. First, let’s explore the Malaysian society in which they live. As of 2023, the population of Malaysia is approximately 33.5 million (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2023). Islam is the national religion, but the federal constitution guarantees freedom of belief in other religions. Citizens are categorized into ‘Bumiputera,’ ‘Chinese,’ and ‘Indians.’ Bumiputera consists of Malays, who are Muslim, and other indigenous people. According to 2020 estimates, Bumiputera accounts for about 69%, Chinese about 23%, and Indians less than 10% (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2020).

The ethnic composition of the Malaysian population (created by the author based on Department of Statistics Malaysia 2020).

Location of Malacca, a key settlement of the Peranakan Indians (Created by the author using Google Maps).

Who Are the Peranakan Indians?

In Malaysia, there are also communities that do not fall neatly into the three official ethnic categories. One such group is the Peranakan Indians, who have formed their own distinct community while maintaining harmonious relationships with other ethnic groups. The term Peranakan derives from the Malay word anak, meaning “child,” and refers to the locally born descendants of foreign settlers. Various Peranakan communities exist in Malaysia, including Chinese, Arab, and other origins.

Among them, the Peranakan Indians are the descendants of Tamil Hindu traders who arrived in Malacca during the 15th century and gradually assimilated into the local society. Their community includes people from various caste backgrounds, such as Chitty, Pillay, Naiker, Rajah, Padayacee, Mudaliar, and Patter, though caste distinctions are not strongly observed. For example, leaders of the committee are elected without regard to caste.

The Peranakan Indian community has historically maintained its religious and social cohesion through the joint ownership of ten Hindu temples, including the Sri Poyyatha Vinayagar Moorthi Temple, which was built in 1781 and is considered the oldest Hindu temple in Malaysia. In addition to managing these temples, the committee have also owned approximately seven acres of surrounding land, which has been leased at affordable rates to Peranakan Indians. This land has long served as a crucial centre for their communal and religious activities, reinforcing their cultural identity and collective cohesion.

Sri Maha Mariamman Temple, one of the Hindu temples owned by the Peranakan Indians (Photographed by the author, May 2024).

Since the 1950s, the committee began renting the land not only to Peranakan Indians but also to other ethnic groups at affordable rates. As a result, people from other ethnic backgrounds, besides Peranakan Indians, started to settle there. For example, in 1976, the composition of 98 households was 27 Peranakan Indians households, 52 Chinese households, 17 Indian households, and 2 Malay households (Narinasamy 1983: 253). Peranakan Indians deepened their relationships with other ethnic groups, and by the 1970s, exogamy had become more common than endogamy. Specifically, between 1966 and 1976, the attributes of spouses of Peranakan Indians in Malacca were 20 Peranakan Indians and 34 non-Peranakan Indians (20 Indians, 5 Malays, 6 Chinese, and 3 non-Malaysians) (Narinasamy 1983: 260). Even today, marriages with non-Peranakan Indians are common.

Cultural Characteristics

The Peranakan Indians have developed a unique hybrid culture, influenced by diverse cultures such as Chinese and Malay. For example, many of them use a language that mixes Malay with Chinese and Tamil in daily conversation. They enjoy not only Indian dishes like Dosa and Idly, but also meals using local spices, herbs, and coconut milk. For clothing, they wear traditional Indian attire such as Sarees and Punjabi suits when visiting Hindu temples, but they also wear Kebaya, a local traditional outfit.

Peranakan Indian women wearing Kebaya.

(https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=990128953160674&set=pcb.990128976494005)

Hindu Temple Festivals

Most Peranakan Indians are devout Hindus and celebrate various religious festivals, including Ponggol, Shivaratri, Varusa Pirapu, Navaratri, and Deepavali. The most important festival is the Dato Chachar festival, held at the Sri Maha Mariamman Temple. The festival, which has been held annually for ten days, attracts thousands of participants (Pillai, 2015), including Peranakan Indians who have moved away from Malacca, other Indian Hindus, and a significant number of Chinese attendees.

During these celebrations, they engage in severe practices (Kavadi), such as piercing their bodies with spears or carrying milk pots in processions, to show their gratitude for the fulfilment of vows to the gods. They also make donations of money, rice, and cooking oil. In addition to seeking healing for chickenpox, they also seek various other spiritual blessings. Among the devout believers, some are possessed by the Gods.

Scene from the Dato Chachar festival in May 2024 (Photographed by the author).

Ancestor Worship

Peranakan Indians practice distinct forms of ancestor worship. Unlike many other Hindus in Malaysia, they primarily follow burial customs rather than cremation. The committee jointly owns and manages a cemetery in Malacca, where most of their ancestors are laid to rest.

During the Margali season, which occurs around December, Peranakan Indians wake up early each morning to pray and place hibiscus flowers at their doorsteps to welcome the spirits of their ancestors into their homes. After that, in January, they visit the cemetery for a ritual known as Naik Bukit, a practice influenced by the Chinese Qingming Festival. During this ceremony, families gather to clean the graves, decorate them with flowers, and offer meals served on banana leaves, including Indian dishes, local sweets, and foods that were favoured by the deceased.

In addition to the Naik Bukit ceremony, families observe a biannual food offering ritual known as Parchu. During Parchu, a variety of dishes, including shrimp, chicken, seasonal fruits, and sweets, are prepared and offered to the spirits of their ancestors. The first Parchu ceremony takes place in January, while the second is held between June and July, coinciding with the fruit harvest season.

Food offerings for ancestors during Parchu. (https://melakachetti.com/important-occasions/)

Conclusion

The Peranakan Indians have developed their community through the committee, which manages both land and Hindu temples. Their religious festivals and ancestor worship rituals not only serve to strengthen their internal communal ties but also provide important opportunities for interethnic exchange with other Malaysian communities. By nurturing and adapting their cultural heritage while engaging in interactions with other ethnic groups, they have developed a dynamic and inclusive identity that continues to shape their role in Malaysia’s multicultural society.

References

Narinasamy, Karpaya. 1983. “The Melaka Chitties.” In Sandhu, Kernial Singh, Paul Wheatley, Abdul Aziz bin Mat Ton, and Institute of Southeast Asian Studies,eds. Melaka:The Transformation of a Malay Capital, c. 1400-1980: 239-263. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

Pillai, Patrick. 2015. Yearning to Belong: Malaysia’s Indian Muslims, Chitties, Portuguese Eurasians, Peranakan Chinese and Baweanese. Singapore: Iseas-Yusof Ishak Institute.

Leave a Reply