Abstract

This paper explores the rise of the gig economy in India. It outlines the contradiction between the rampant existence of digital platforms on the one hand and the low availability of labour rights and protections to workers on the other. However, the kind of engagement via such platforms grants the workers some flexibility; other fundamental rights are usually stripped away, like receiving full health benefits, contracts with written terms, and better grievance redress mechanisms. This qualifies platform work driven by algorithms under the concept of Decent Work established by the International Labour Organization, which this research will use to demonstrate how this type of work serves in perpetuating informality, especially among urban migrants, lower caste populations, and women.

Citing the example of a real-life situation of one of the food delivery workers in Delhi, the paper explains that the symbolic inclusion presents itself when organised exclusion is still in place. It emphasises that the provision of statistical representation should be accompanied by substantive rights assurance. Accordingly, the paper offers the following SMART policy recommendations for fostering a more inclusive and rights-based approach to digital employment: adding to the discussions on labour justice in the platform economy and, simultaneously, assisting India in achieving Sustainable Development Goal 8 agenda.

Keywords: Gig Economy, Informal Labour, Social Protection, Decent Work, Platform Workers, Labour Law in India

Introduction

Over the last few years, the dynamic workplace in India has undergone a significant change, and the gig economy has emerged almost overnight. It is a short-term, freelance job operated on a digital platform that usually has no specific contracts undertaken, and no obligation by the employer. Popular mobile applications such as Uber, Zomato, and Urban Company have provided flexible income opportunities, particularly to young people and migrants in urban areas. Nevertheless, the concerns relate to such jobs, including job insecurity, the absence of social securities, and weak legal protection (NITI Aayog, 2022).

The International Labour Organization (ILO) describes decent work as work that ensures fair remuneration, employment security, social protection, decent treatment in the workplace and the capability of exercising social dialogue (ILO, 1999). Most of these protections are absent in the Indian gig economy. Workers’ identity is also commonly referred to as self-employed workers or independent workers. It will not be entitled to paid leaves, accident insurance, maternity benefits, and pensions. Most individuals are exposed to algorithmic control, fluctuating income, and customer ratings-related stress, and they often have insecure and unstable jobs (ILO, 2021).

Estimates by the government representatives indicate that 7.7 million individuals were employed in the gig economy in 2020-21 and that this figure is projected to increase to more than 23 million by 2030 (NITI Aayog, 2022). A significant proportion of these labourers belong to the vulnerable sections, such as Scheduled Castes, Other Backwards Classes and migrants. Moreover, more women are working in platform-related work in the care and service industries, where they are increasingly exposed to security threats, domestic non-payment and discrimination at platforms (Srivastava, 2020). The digital divide also makes most workers unable to access government welfare schemes or complaint systems.

Also in 2020, the Indian Parliament enacted the Code on Social Security, and this was the first time the concept of gig and platform workers was officially recognised. The law, however, neither provides any explicit obligations by platforms as employers nor outlines how the social protection is to be funded or delivered. Although platforms such as the e-Shram portal have been introduced to enrol informal workers, they have had minimal effects because of little awareness, the digital divide, and poor inter-institutional coordination (Ministry of Labour and Employment, 2022). Gig workers are also not covered by welfare boards such as the Building and Other Construction Workers (BOCW) board, primarily due to the unresponsiveness of the existing eligibility conditions and the absence of universally accepted evidence of work (Ghosh, 2022).

This chapter reviews the availability of decent work for gig workers in cities in India and what available legislation, government programs, and online spaces offer. It is dedicated more to the way caste, gender issues, informality, and digital exclusion are impacting the experiences of these workers. Still, it also examines India’s commitments to international labour standards. Based on the field-based expertise, the official reports and the ILO conventions, the chapter offers some policy recommendations that can enhance the protection of this growing workforce. This is meant to ensure that gig work may be safe, inclusive, and attuned to Sustainable Development Goal 8, which calls for the need to promote decent work and economic growth, inclusive of all.

Section 2: Literature Review and Key Definitions

In the last ten years, the gig economy has become an object of discussion and research within the sphere of development and labour studies, particularly with the reshaping of informal labour in India’s cities due to the influence of digital platforms. It has been noted that just like the traditional informal work, platform-based jobs come with several associated risks, yet they also confer the opportunity of getting income to low-skilled and semi-skilled workers (Breman, 2013; Srivastava, 2020). The new form of digital casualisation formed through app-based work falls outside the scope of the current labour laws and protection through trade unions. As ILO (2018) defines informal work, it is a job that lacks legal contracts and social security. India’s prevailing type of work occupies over 83 per cent of the labour force (PLFS, 2023).

According to the early research conducted by Jan Breman, insecure and unstable work was something that was a reality for migrants and lower caste workers in Indian cities. He defines the informal economy as an unfree area where workers cannot live with certainty, are dependent, and cannot receive care from the institutions (Breman, 2013). The same conditions can be observed in the gig economy, where employees can use apps and smartphones. However, they still lack access to basic amenities like medical leave, accident insurance, or pension plans. Ravi Srivastava (2020) points out that platform jobs do not eliminate insecurity but transform it since they function based on algorithm-based control, unpredictable wages, and computerised management. Gig workers are managed not by individuals but by the programs and scores given by customers, which are often unjust and out of their control.

The limits of platform-based work have also been discussed in worldwide investigations by the ILO experts. The World Social Protection Report (ILO, 2021) notes that gig workers are commonly mislabeled as independent contractors. This enables these sites not to have to pay for insurance, pensions, or other remunerations for workers. The report also emphasises that the informal nature of the employment relationship makes it more challenging to find redress through the courts, join unions, or seek legal assistance.

International comparisons further reveal how countries are beginning to grapple with the regulatory challenges of platform work. For example, Brazil has introduced a digital tax on platforms to fund the benefits of informal workers, including ride-hailing and delivery workers (ILO, 2022). Indonesia has implemented a mandatory social security scheme for informal workers, including those in the gig economy, financed through mixed public-private contributions. Meanwhile, through legal cases such as Uber BV v Aslam (2021), the United Kingdom has classified platform workers as “workers” rather than self-employed contractors, granting them access to minimum wage, paid leave, and collective bargaining rights. These comparative cases offer insights into how legal recognition, funding models, and institutional reform can create more inclusive digital labour systems.

Regarding technological control, recent scholarship highlights the deeper algorithmic vulnerabilities experienced by gig workers. De Stefano & Wouters (2022) argue that algorithmic management can act as an invisible employer, creating a “surveillance without accountability” regime where decision-making is automated and opaque. Woodcock and Graham (2023) similarly describe the global platform economy as a “digital Taylorism,” where workers have little control over task allocation, wages, or work conditions due to constantly shifting algorithms and consumer ratings. These studies show how platform architecture fragments labour protections and reconfigures the power dynamics of employment relationships.

In India, the fact that labour legislations are not enforced well and that informal workers were historically not included in major labour reforms exacerbate all these problems (Ghosh, 2022).

Jayati Ghosh (along with Uma Rani and Amit Basole) has produced Indian economists who have also demonstrated how gig work widens social inequalities based on caste, gender, and access to digital infrastructure. According to Ghosh (2022), most gig workers earn less than the minimum wage, and they are driven by fluctuations in their income baseline by the alteration of algorithms or policies of the given platforms. Other burdens include unpaid household work, safety issues during travel, and additional loads placed on women workers, particularly those in the care and domestic service. These concerns are based on the results of a study conducted by the Centre of Equity Studies (2021), according to which a large number of migrant gig workers reside in poor housing, lack official documents, and are excluded from welfare programs due to the gap in documentation and identification.

In this light, explaining some of the essential concepts to be adopted in this chapter is necessary. The gig economy is the name given to the industrial system of labour where employees work temporarily; specific requirements and tasks are determined primarily through online tools. Such employment opportunities include ride-hailing, food delivery, domestic, online freelancing, and couriering. Although a few of its workers might just work off-network, most rely on the platforms to get consumers and have their work assigned. Comprising traditional daily-waged labour together with digitally mediated work with no formal contracts, grievance redress, or social protection, the term informal work in this context connotes not the formality of the contract where the two parties may be unaware of each other, but their digital accessibility through any of the many forms of online access to the labour market.

Another essential concept is digital exclusion, which means workers cannot navigate or access digital services because they do not have an internet connection, smartphones, language issues, or digital literacy. The inability to learn app-based rules or avoid changes according to the algorithm leads to discrimination or suspension without a complaint from many gig workers. Welfare boards are state-level institutions, such as the Building and Other Construction Workers Welfare Board (BOCW), which is built on the principle of providing social protection to unorganised workers. Nonetheless, such schemes may not cover gig workers in many cases because of obsolete employment classifications and a lack of a clear understanding of platform-based employment.

The other difference relevant to this analysis is between social security and social protection. Social security includes typically contributory programs such as pension or medical insurance coverage funded through contributions from an employer and a worker (e.g., Employees Provident Fund, ESI). By contrast, social protection embraces other non-contributory programs, including public health, maternity, or cash payments to vulnerable groups (ILO, 2017). Edging into these two frameworks are gig workers as they occupy this grey area. Although not in the workforce, they are not eligible for most government welfare programs unless explicitly enrolled. Specifically, Recommendation 204 (2015) of the ILO urges member states to include informal workers in formal social protection schemes with the help of inclusive reforms of policies.

Concisely, the current academic and policy literature paints the picture of the gig economy as both a space of opportunity, inequality, and regulatory failure. Informalisation is set to take new shapes, and until the platform workers can be officially considered a profession and are entitled to the same protections, the vision of digital empowerment will not be available to the vast majority. In this chapter, based on this body of literature, I examine how India’s present labour reforms and welfare mechanisms can be restructured to make them inclusive, fair and decent work for this burgeoning workforce.

Section 3: Methodology

The chapter contains a qualitative, analytical study of the conditions of gig workers in urban India that reflects on social protection and decent work agendas in a specific manner. The analysis undertaken is mainly that of a secondary source of research, where government reports, labour statistics, academic literature, policy documents, and international standards published by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) and NITI Aayog, Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) and e-Shram Portal were reviewed. These reports provide credible, national representative evidence regarding the dynamic character of India’s informal and platform-based work (NITI Aayog, 2022; PLFS, 2023; ILO, 2021). The data used and analysed contains the central and state-level data to study informality, welfare access trends, and regional policy gap variation.

The chapter will use a realistic case study to supplement the secondary data, with the case study relying on field experience and practical work with the urban informal worker in the context of the earlier research and internship experiences. Though pseudonymous and representative in type, the chosen case looks to the real-life problems of migrant gig employees in the Delhi-based platform economy. The case provides the ability to fill that gap between policy documents and experiences and gives a human voice to the bigger data-based story. Such descriptive qualitative information plays a vital role in recognising the daily exclusions and systematic problems, which are usually hidden in aggregate statistics (Srivastava, 2020).

The sampling method applied to the case study was convenience because it was observed among workers who could be accessed easily during previous studies and surveys held in Gurugram and Delhi, India, urban construction and service regions in 2023-2024. This was done because this work is informal, mobile and not institutionalised, making random sampling a waste of time (Creswell, 2014). This was not about statistical generalisation but rather deep contextual details of the life of one worker representing the situation of an entire industry. Such ethical considerations raised during the narrative’s development included voluntary participation, protection of their identity and revealing personal data.

The methodological approach is taken to the ILO Decent Work Agenda, a conceptual guide and an analytical tool. The analysis structure in the following sections shows four pillars of decent work: employment generation, social protection, rights at work, and social dialogue. Under this approach, gaps in the coverage of labour protections to gig workers are discovered, and the areas that would require institutional reforms are also determined. Intersectionality is also applied in the chapter as it evaluates the combination of caste, gender, migration status, and digital access in the access of workers to rights and welfare (Ghosh, 2022).

Although this research uses much published information and institutional reports, limitations exist. Due to ethical sensitivity, the study did not have time to conduct in-depth interviews with platform companies or government officials. Besides, though the convenience sampling technique is helpful in terms of depth of interpretation, not all regional and sectoral differences in the gig economy are covered. There may not be the voices of the transgender persons, access to differently abled individuals who work in small towns of India, which places limits on the generalisations of findings. Nevertheless, even the mixture of the empirical understanding, the review of policies, and grounded theory provides space to make meaningful conclusions and realistic policies.

Section 4: Contextual Background and Realistic Case Study

The urban labour market of India has transformed with haste over time, particularly in the wake of the pandemic, when digital platforms began to serve as the core source of income to millions of informal workers With no job growth in the formal economy, gig and platform jobs have become the resort of many members of the population, especially young people, rural migrants, and the victims of the partial or complete decline in such sectors of the economy as construction or manufacturing. In cities such as Delhi, Bengaluru, Mumbai, and Hyderabad, the number of individuals involved in ride-hailing, food delivery, domestic services, and e-commerce logistics has sharply grown (NITI Aayog, 2022). Nevertheless, although these employments offer an alternative to unemployment, they hardly allow income security, work safety, or access to long-term social protection.

The majority of platform workers exist beyond some arrangement of employer and employee. Platforms such as Uber, Ola, Zomato, Swiggy, Urban Company call their workers partners or independent contractors to be relieved of the legal obligation to pay wages, insurance and welfare contributions. Such legal vagueness imposes the full risk of accident or ill health on the employee. Take the case of a delivery worker, who might also wear a branded t-shirt and go everywhere reading app-based instructions like an employee, but does not have the right to take paid leave, health insurance or retirement pension. In addition, language and literacy areas cause significant parts of workers to be unaware of platform contracts, terms of service, or payment frameworks (Srivastava, 2020).

An example of such realities on the ground can be seen using the following real-life story. Rajesh is a 28-year-old Bihari migrant who shifted to Delhi in 2018 to seek work as a construction labourer in his home village. Having worked at first as a thekedar (contractor) employee with daily wages, he became part of a food delivery service as construction jobs disappeared due to the COVID-19 lockdown. Rajesh is working 11 hours on average, riding his bicycle 70-90 km daily and earning 450-550 rupees daily. The company does not provide him with a petrol allowance, insurance, or health coverage. In 2023, Rajesh was involved in a road accident that affected his ankle. He did not carry any medical insurance and had to borrow 8,000 rupees in kind donations from another rider and thus could not work for two weeks. The platform did not support him financially, nor did it guarantee him any job security. His ratings remained lower when he resumed, and he made fewer orders and fewer profits.

Rajesh is neither registered by the e-Shram portal nor the BOCW welfare board. He has heard of these schemes but never availed himself of them because he is uninformed, fearing that he would lose working time and get confused over the terms of eligibility. Rajesh shares a one-room flat with two other fellow riders. He has no ration card in Delhi and sends money home to his parents. His case indicates an even broader conflict of all the urban gig workers in India: informality, precarity, and invisibility despite providing the necessary services within the city. Rajesh does have a smartphone and works via an app, yet he does not have access to the digital world that offers him protection and dignity.

Rajesh is not an exceptional story; similar stories are becoming increasingly common. Gig work informality is economical, social and legal. The migrants and low-caste workers encounter additional challenges because of a lack of documentation, discrimination, or inability to express their concerns online. Female gig workers who work in social care and beauty services, in particular, conceal their jobs when judged by their families through the stigma of gig workers and receive no harassment support system. However, the Gig economy, as a form that is seemingly contemporary, resorts to the older orders of caste, gender, and informality in a different digital avatar (Ghosh, 2022).

This case study also shows an urgent need to regulate app-based labour. It also reflects how the policy neglect and welfare delivery were done in bits and pieces, and the human cost of this neglect is also reflected. The remaining parts of this chapter will explain how existing labour codes, social protection systems and international standards interact with such realities and what needs to be reformed to respond to them.

Section 5: Data Analysis – Informality, Welfare Access, and the Gig Workforce

Although India’s gig economy is expanding at an impressive rate, it remains firmly integrated into the rest of the informal labour market. A recent Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS, 2023) report informs that the social protection schemes do not cover more than 83 percent of the working-age Indian workers who are informally employed. Most of the informal workers in the city (House workers, delivery workers, and freelance workers, etc.) work now using digital platforms, where they manage to be hired as ride-hailing, food delivery, home services, and freelance workers. Even though they help provide necessary urban services, such workers fall out of most labour welfare systems as they are not covered by the law, often rely on the platform and are poorly controlled by the state (ILO, 2021).

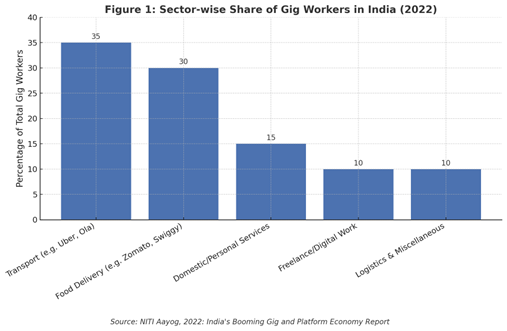

According to the NITI Aayog report (2022), gig and platform workers were estimated to be 7.7 million in 202021 and 23.5 million in 2030. The sectoral concentration is not even as represented in Figure 1, where gig workers are nearly 35 percent as transport-related services users (e.g., Uber, Ola), 30 percent as a food delivery provider (e.g., Zomato, Swiggy), 15 percent as personal/domestic service providers, 10 percent as freelance and digital worker and the remaining 10 percent in logistics, warehousing and odd jobs. This focus shows that platform-based consumption activities in Tier-1 and Tier-2 cities mainly facilitate gig work.

Figure 1: Sector-wise Share of Gig Workers in India (2022)

Source: NITI Aayog, 2022: India’s Booming Gig and Platform Economy Report

Transport and food delivery comprise most of the gig sector in India: they make up over 65 percent of platform-mediated jobs. This indicates that urban orientation in services is based on consumption.

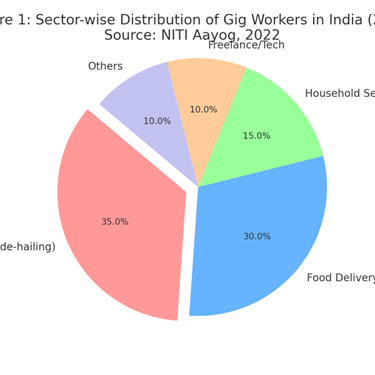

Figure 2: Sector-wise Distribution of Gig Workers in India (2022)

(Estimated Share based on NITI Aayog, 2022)

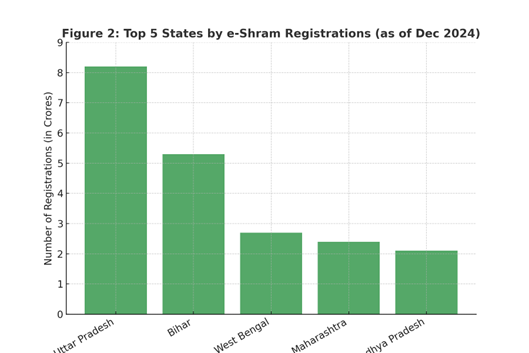

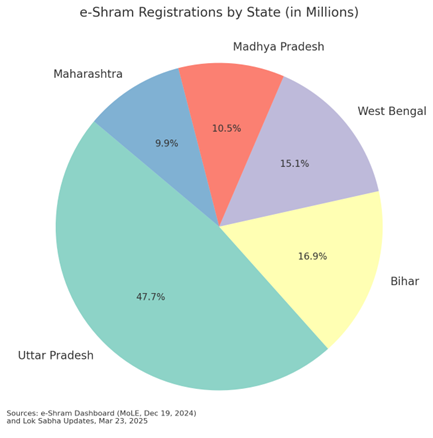

In order to examine access to social protection, we resort to the e-Shram Portal, the first national registry of unorganised workers in India, launched in 2021. By the beginning of 2024, more than 28 crore workers will be registered, but only a small percentage will occupy jobs based on gigs and platforms. The table below contains a comparison snapshot of some urban concentration-based states where gig work is highly evident.

Figure 3: Top 5 States by e-Shram Registrations (as of Dec 2024)]

Source: Ministry of Labour & Employment, e-Shram Dashboard, 2024

Uttar Pradesh and Bihar have the highest e-Shram registrations, showing that more people have reached these areas. Nevertheless, the gig worker enrollment proportion is unevenly low, particularly in urbanised states like Maharashtra and Delhi.

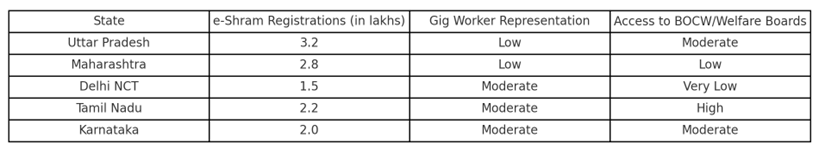

Table 1: e-Shram Registrations and Welfare Access in Selected States (2023)

(Compiled from Ministry of Labour & e-Shram Dashboard, 2023).

Figure 4: Share of e-Shram Registrations by Top 5 States (as of Dec 19, 2024)

Source: Ministry of Labour & Employment (e-Shram Dashboard), Government of India & Lok Sabha Updates (March 23, 2025).

Although the level of informality in cities is high, and the level of digital literacy is high in states such as Karnataka or Delhi, the active enrollment in welfare boards is low among the gig workers. This indicates the absence of awareness of schemes, documentation challenges (the impossibility of correcting the mismatch between the address of residence and identification data), and coordination between platform companies and government agencies (Ghosh, 2022).

Another problem is the inability to be transported and interoperable between welfare systems. High rates of movement across cities or change of platforms by many gig workers mean there is a massive difficulty in ensuring reasonable access to health benefits, insurance, or pension-like provisions. Whereas the Commission has recommended including gig and platform workers in the Code on Social Security (2020), it has been very weak and spread out with no specific institutional organisation to oversee the process (Ministry of Labour & Employment, 2022).

In addition, the gig workforce is also characterised by stratification based on caste, class, and migration. The number of employees in delivery and transportation services who are members of Scheduled Castes and Other Backwards Classes is high, with comparatively low vertical mobility and excessive vulnerability towards economic realities that depend on the platform incentives (Srivastava, 2020). There is no disaggregated information on social groups in the gig economy, which poses a challenge to the effective formulation of targeted welfare and the possibility of tracking exclusion.

Using the ILO’s Decent Work framework, it is evident that gig workers experience deficits across all four pillars:

- Employment security: Work is uncontracted, volatile, and seasonal.

- Rights at work: No formal grievance mechanisms, union representation, or protection from deactivation.

- Social protection: Limited coverage through schemes like e-Shram or state boards.

- Social dialogue: Absence of tripartite discussions involving workers, platforms, and government.

This paragraph indicates that although India has already achieved some progress in developing digital databases and legal frameworks, the actual inclusion of gig workers into the realm of possibilities is much further than it is. The subsequent parts will analyse how the international labour standards and the codes on labour in different countries can provide more equal protection.

Section 6: Legal and Institutional Gaps – Labour Codes and ILO Conventions

Although India has made certain legislative efforts to identify the needs of gig and platform workers, the policy has primarily been implemented, as the vision is much different from the implementation. The latest legal system that deserves the most attention is the Code on Social Security, 2020, which, on paper, covers gig workers and platform workers by guaranteeing them social security benefits for the first time. However, in real practice, the effectiveness of this code is low thanks to unclear definitions, inability to understand clear financial authorities, and poor mechanisms of its enforcement (Ministry of Labour and Employment, 2021). The legislation allows the central government to design welfare programs, but it does not require registration and contribution from platform companies. It neither tells the minimum levels of coverage nor the redressal mechanisms of grievances.

It is also common for platform apps to display one vehicle model during booking, while the worker arrives with a different two-wheeler. In accidents or injuries, companies often deny insurance coverage by arguing that the vehicle used was not officially registered on the platform. This practice creates serious legal and safety risks for workers and consumers, exposing the gap between app-based representations and real-world accountability.

With the code, gig workers are now defined as anyone who engages in a work arrangement or undertakes work, and gets paid through that arrangement, and does not qualify under the traditional job of an employer and employee, which means that platforms can still refer to gig workers as partners or contractors, which has the effect of evading responsibility. Outcome is a grey area in the law with the workers not being protected by the Industrial Disputes Act, Minimum Wages Act, or Occupational Safety, all of which laws do not cover them, but still face the company’s ratings, rules, and penalties (Srivastava, 2020). When no particular laws govern the platform’s responsibility, the contribution to any social security fund is optional or nil.

Furthermore, even the e-Shram portal, suggestive of a fine move towards creating a commonplace record of the unorganised workforce in the country, is yet to be merged into state welfare structures or the one under the Social Security Code. Most part-time workers do not know about their rights, or these workers cannot be registered, as they lack documentation, such as Aadhaar-linked bank accounts, proof of working, or residence in the state (Ghosh, 2022). Among the registered participants, most people do not get access to benefits such as accident covers, maternity assistance, and skills training because of institutional blockages.

The International Labour Organization report (2022), Digital Labour Platforms and the Future of Work, focuses on the importance of well-established platform roles. It recommends that governments legitimise the position of platforms as employers or quasi-employers, so that they contribute to social security systems, so that data can be observed, and grievances can be addressed. The report also helps establish a group of dependent contractors, especially in legal terms, by inventing a class of workers dependent economically on one platform, but not in full employment. Such countries as Canada and Italy have placed a bet on this model so that flexibility could be accompanied by precautionary measures such as minimum wages and accident insurance (ILO, 2022).

As opposed to such global road maps, India has no legal framework. Even though the Code on Social Security (2020) symbolises the gig worker, the platforms do not provide responsibilities that can be enforced. Therefore, the protection of the worker is advisory rather than binding. The European Union had, however, made a step towards making the regulations more enforceable with the expected Platform Work Directive. This direction has a rebuttable presumption of employment when some aspects of control are present, such as algorithmic control or the determination of price levels by the platform. In this provision, it becomes the platforms’ responsibility to prove that the worker is independent. Without such laws, India may fail to apply work fairness in the gig economy.

From an international perspective, India’s legal framework also falls short of global labour standards. The International Labour Organization (ILO) has several conventions and recommendations relevant to the protection of gig workers, including:

- Convention 102 on Social Security (Minimum Standards)outlines comprehensive coverage across healthcare, unemployment, injury, maternity, old age, and family benefits.

- Convention 155 on Occupational Safety and Health mandates workplace safety, accident prevention, and employee health rights.

- Although aimed at household work, Convention 189 on Decent Work for Domestic Workers provides a valuable precedent for extending dignity and rights to informal and marginalised sectors.

- Recommendation 204 on the Transition from the Informal to the Formal Economy urges governments to recognise and progressively formalise informal workers through legislation, protection, and dialogue (ILO, 2015).

India is not a party to most of these conventions, especially to C102 and C155, which restrict its legal obligation to wide-scaled protection of informal and platform workers in labour. Even when the principles act in the same direction, like in the case of considering the gig workers under the 2020 labour code, there is a lack of persistence and institutional clarity that negates efficiency. ILO has also stressed the significance of social dialogue or tripartite negotiation among the government, employers and workers’ organisations. The gig economy in India is a case where such a conversation does not exist, and nobody has any legal platform where bargaining is done by a broad group of gig workers or even where an actor can present complaints.

The other area where there is a significant gap is the role played by trade unions and employers’ organisations. Platform workers are a recent development in terms of the traditional unions being able to engage with them, and the scattered, piecemeal and highly digitalised nature of gig work makes it hard to organise it. On the other hand, employer organisations representing platforms say the flexibility and empowerment of platform work can be lost with formal labour standards, which may disincentivise innovation or job creation. This ideological tug-of-war has led to policy paralysis and the exclusion of workers.

Lack of a well-regulated body or a specific tripartite body to oversee the gig labour workforce has implied that state initiatives like health insurance plans or welfare boards have only been implemented haphazardly and have little effect. For example, some gig workers have been incorporated into the BOCW-like programs in a state borderland like Tamil Nadu. In contrast, states like Delhi lack the institutional constructs to regulate the platform-based employment securities (e-Shram, 2023). Such an institutional gap gives rise to a legal vacuum and policy fragmentation.

To conclude, although India has symbolically taken some steps toward recognising gig workers, the legal and institutional frameworks are insufficient. Convergence of national labour code and ILO documents is an urgent necessity, particularly regarding classification of workers, sources of social insurance, occupational safety and resolving disputes. Without such structural changes, gig workers will remain those who fall between the cracks and appear in economic growth statistics but cannot be seen by the law and justice.

Section 7: Policy Recommendations – SMART and Actor-Based Reforms

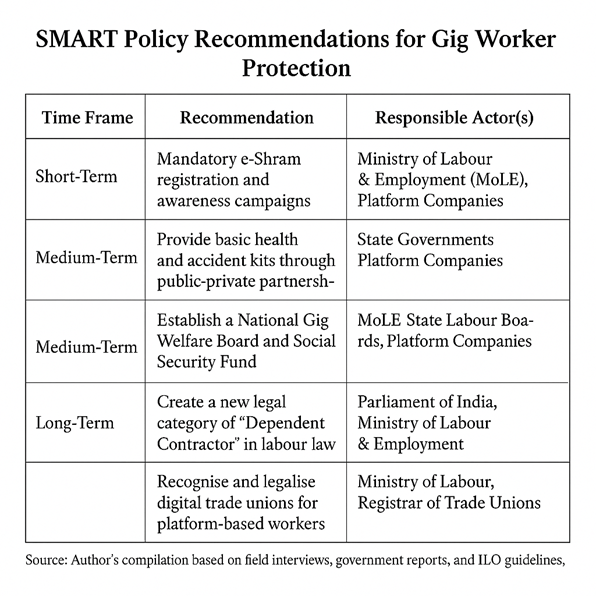

The increasing number of people and levels of exclusion, informality, and insecurity in India should be addressed through legally binding protections as policy responses to go beyond the symbolic recognition. This will call on short-term, medium-term, and long-term SMART measures, that is, Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound, and the cooperation of various agents, such as the central government, the state governments, platform companies, the association of workers, and trade unions.

Short-term (0-1 year) interventions must be based on direct inclusion and awareness. A compulsory registration campaign must be initiated using e-Shram and the incorporation of the local labour departments. This would ensure that the workers on the gig and platforms are provided with accident insurance, health plans, and emergency resources. The Ministry of Labour must partner with such platforms as Zomato, Swiggy, Ola, and Urban Company to work out the regional targeted awareness campaigns in regional languages. The registration process might be related to logging into the app and rewards systems, guaranteeing their voluntary adoption and high coverage (Ministry of Labour and Employment, 2023).

There also needs to be a Basic Protection Kit for platform workers, which would cover accident insurance, health insurance and emergency cash provision and be co-financed by the state and platforms. This would bring the provisions of Section 114 of the Social Security Code to life, giving the government access to notify welfare schemes of gig workers (Srivastava, 2020). All workers registered on e-Shram should be given a digital job ID (attached to their mobile number and bank accounts) to make it portable between platforms and cities.

The medium-term (13 years) objectives should establish institutional social protection frameworks. A National Platform Workers Welfare Board is to be constituted with the help of representatives of ministries, state governments, gig companies and workers organisations. A Platform Social Security Fund should be maintained through compulsory contributions of platforms on an agreed percentage of their gross income (e.g., 12%), or several workers employed (e.g., 12 workers), and administered by this board. The international examples could include the digital labour tax scheme in Brazil or the insurance funds for the informal workers in Indonesia (ILO, 2021).

Also, the already established BOCW welfare boards can be extended to cover the platform workers by considering reforms on the eligibility criteria. Already, these boards are offering maternity aids, death/disability aids and housing grants to workers, whose construction is informal. Subject to a few changes at the administrative level, parallel plans can be proposed to gig workers enrolled on e-Shram. There should also be a requirement that platforms release transparency reports on workers’ remunerations, safety, and grievance redressal performance every quarter, which independent bodies should audit.

The focus of long-term (3- 5 years) structural changes should be directed to altering the employment status of platform workers. India can develop a third category of contractor law that is a dependent contractor, which is being followed by many EU states, and they have certain benefits of an employee, but without affecting the flexibility of the other aspects of work. Then, workers would be able to experience minimum wage protection, safety at the workplace, and access to courts in case of unfair dismissal or algorithm discrimination (Ghosh, 2022).

India can institutionalise voice and representation by allowing digital trade unions of gig workers to be registered and formalising the federation of platform-based workers like the Indian Federation of App-Based Transport Workers (IFAT). These unions should be represented on any labour advisory board discussing gig work. Further, a platform ought to be obligated to develop feedback and grievance channels in their app that are put under scrutiny by autonomous supervisors.

The civil society has an equal importance to play. It should incentivise NGOs operating in the urban areas of informal settlements to help the gig workers complete documentation, digital access, and utilisation of schemes. Pilot projects may be carried out through the funds of donor agencies like the ILO, UNDP, or charitable foundations, to assist women gig workers in mobility, digital security, and protection against harassment at work.

Recommendations Summary

There must be a multi-actor, multi-stage approach to breaking the arena of platform work into social justice and accountability to the law. These reforms should be discussed with employees and formulated to align with India’s commitments to Sustainable Development Goal 8 and the concept of Decent Work developed by the ILO. Unless accompanied by such interventionist and time-limited measures, the digital labour to be provided to millions of the most vulnerable urban workers and populations will remain a mirage.

Section 8: Conclusion

In India, the gig economy is both a change in the structure of employment and a product of pre-existing inequalities in the labour market. Although online platforms provide changes in forms of flexible labour, especially in the cities, they have recreated and exacerbated most of the vulnerabilities that informal workers used to experience. The current state of gig workers lacks fundamental employment protection, a signed contract, social security, and a workable grievance system. Their exposure in the market facilitated by apps and ratings is juxtaposed with their nonexistence in welfare state and market policies and governance (Ghosh, 2022).

The government’s inclusion of gig and platform workers in the Code on Social Security (2020) was a symbolic development. Nonetheless, this addition is rather wishful without specific funding, enforcement and rules of institutional responsibility. The platforms still enjoy some legal grey areas that enable them to manipulate workers by algorithm and deny their employers their responsibilities. Meanwhile, the welfare systems such as the e-Shram card, BOCW boards, or social security schemes at the state-level are still not seamless, poorly coordinated, and unavailable to a significant proportion of gig workers, mostly migrants, women, and members of the marginalised castes (Srivastava, 2020; ILO, 2021).

This chapter has revealed that Indian gig workers are subject to gaps in all four pillars of the Decent Work paradigm, including employment security, social protection, workplace rights and social dialogue, using it as an analytical framework. Although the sector has been growing very fast, there has been no improvement regarding the active involvement of workers in decision-making or the development of legal frameworks that safeguard workers’ dignity and livelihoods. Although the language is progressive, current laws are unclear in their operation, and there is a lack of political will and coordination among stakeholders.

India is not very active internationally regarding the main ILO conventions like C102, C155, and C189. It is slow to take up Recommendation 204, undermining its capacity to develop inclusive and enforceable protection rights for gig workers. Worldwide best practices present valuable cases to learn: Taxing online platforms when it comes to the Brazilian mandatory levy, insurance systems of informal workers in Indonesia, and the establishment of a third status of dependent contractors in the EU are the models that matter and can be adapted to India (ILO, 2022).

The chapter has recommended short-term SMART and actor-based reforms, including registration drives and welfare packets, to long-term legal recognition and online trade unions. These are real, situation-specific, and in tandem with domestic constitutional principles and internationally acceptable standards in labour practices. More notably, they pay attention to the interconnections among informality, migration, castes, and gender, as well as digital exclusion in determining the nature of gig work.

In summary, the hurdle should not only be to induct the gig workers into schemes and databases, but also to revise what employment and responsibility mean today within the digital realm. Policymakers, platforms, civil society and trade unions should collaborate to develop a rights-based approach that puts the worker, not the user or the investor, at the heart of the future of working. At that point, the digital economy in India will be genuinely inclusive, resilient and aligned to the vision of Sustainable Development Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth for All.

References:

Breman, J. (2013). At Work in India’s Informal Economy: A Perspective from the Bottom Up. Oxford University Press.

Centre for Equity Studies. (2021). Voices from the Margins: Informality, Invisibility, and Injustice in India’s Urban Gig Economy. CES Report.

Ghosh, J. (2022). Platform workers and labour rights in India. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, 65(3), 489–502.

International Labour Organisation. (2015). Recommendation No. 204: Transition from the Informal to the Formal Economy. ILO.

International Labour Organisation. (2017). World Social Protection Report 2017–19: Universal Social Protection to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. ILO.

International Labour Organisation. (2021). Digital Labour Platforms and the Future of Work: Towards Decent Work in the Online World. ILO.

International Labour Organisation. (2022). World Employment and Social Outlook: The Role of Digital Labour Platforms in Transforming the World of Work. ILO.

Ministry of Labour and Employment. (2021). Code on Social Security, 2020. Government of India.

Ministry of Labour and Employment. (2023). e-Shram Portal Dashboard [Data set]. https://eshram.gov.in

NITI Aayog. (2022). India’s Booming Gig and Platform Economy: Perspectives and Recommendations on the Future of Work. Government of India.

Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS). (2022–2023). Annual Report on Employment Indicators. National Sample Survey Office (NSSO), Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation.

Srivastava, R. (2020). Understanding Circular Migration in India: Its Nature and Dimensions, the Crisis under Lockdown and the Response of the State. Centre for Employment Studies, Institute for Human Development.

De Stefano, V., & Wouters, M. (2022). Algorithmic Management and Collective Rights: The Platform Work Directive Proposal and Beyond. European Labour Law Journal, 13(3), 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/20319525221112410

Woodcock, J., & Graham, M. (2023). The Gig Economy: A Critical Introduction (2nd ed.). Polity Press.

ILO (2022). World Employment and Social Outlook: The Role of Digital Labour Platforms in Transforming the World of Work. International Labour Organization.

Supreme Court of the United Kingdom. (2021). Uber BV v Aslam [2021] UKSC 5.

European Commission. (2021). Proposal for a Directive on Improving Working Conditions in Platform Work. COM(2021) 762 final.

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021PC0762

ILO (2022). Digital Labour Platforms and the Future of Work: Towards Decent Work in the Online World. International Labour Organization.

Leave a Reply