In India, migration is not just about moving from one place to another, but a battle for survival and the assertion of one’s identity and dignity. In post-liberalisation India, and even more so now in the times of COVID-19, internal migration is increasingly intertwined with the world of work. For millions of migrants from rural areas heading to cities such as Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, or Hyderabad, gig work on platforms has become one of the few viable employment opportunities. And companies like Zomato, Swiggy, Ola, and Urban Company have built an alternative to the labour exchange, where work is controlled not by people but by algorithms. Their offer is supposed to be one of flexibility and freedom. Still, in practice, it is about precarity and vulnerability, particularly for internal migrants who lack social networks, local newspapers, or legal safeguards in their destination cities.

And more of India’s internal migrants, especially young men from states like Bihar, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh, are turning to app-based gig work. Many are lured by the prospect of fast onboarding, daily wages, and the ability to start earning even without a formal education. Take the case of Ravi Kumar, a 24-year-old migrant who came to Delhi from Samastipur in Bihar in 2021, after he lost his job during the second wave of the pandemic. He currently operates as a food delivery boy with Zomato. At first optimistic, Ravi quickly saw that all was not as it seemed. He usually makes ₹400–500 a day after paying for fuel to a platform — a fraction of what platforms advertise. His workdays are long, his income uncertain, and he doesn’t have a safety net in case he falls ill or has an accident. His story is not unique. It reflects a growing crisis in India’s urban labour markets, where gig work has become the default option for those with limited opportunities.

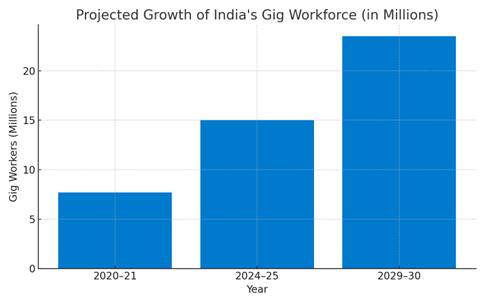

Bar graph showing the projected growth of India’s gig workforce from 2020–21 to 2029–30. Source: NITI Aayog Policy Brief, 2022

The gig economy is advertised as a cutting-edge, empowering alternative to traditional jobs, one especially suited to the new century’s aspiring professional class. But for migrant workers, it more often means labour under opaque systems without protections. Workers sign into apps and accept tasks but have no say in how those tasks are assigned, how their performance is evaluated, or why their accounts might be deactivated. It is the algorithms that run the show, but there is no transparency or redressal. The result is a labour force that never gets far ahead but always manages to scrape by. Gig platform companies categorise their workers as “independent contractors,” exempting themselves from providing benefits such as paid leave, health insurance, and job security. This legal grey area has allowed a bastardised form of employment, where employers can pass their tasks onto workers without any of the responsibilities being shifted from employers to workers, without any corresponding support.

Despite these disadvantages, gig work is preferred over other informal sector work by migrant labourers because it is quicker to access and pays relatively higher, provided one is new to this mode of engagement. No references or interviews are required, and money can be earned from day one. For many, this is preferable to backbreaking daily-wage construction work or long shifts in small factories. The claim of such “flexibility,” however, does not come without a price. Workers are left to take on the risks of road crashes, harsh weather and even police harassment with no access to health care or insurance. Many gig workers in Delhi protested during the 2023 delivery worker protests, which were held against worsening working conditions. They called for fair pay, medical support, and basic dignity. Their protests laid bare the simmering discontent of gig workers and highlighted how deeply the system is failing those it relies on.

The Indian legal landscape has begun to acknowledge the need for reform. The Code on Social Security, 2020, covers gig and platform workers. But the execution is limp. Many workers are unaware of their rights, and the registration rate on platforms such as the e-Shram portal is low. In reality, virtually no gig workers have received any benefits. Social security is tied to formal employment or being locally identifiable, neither of which is common for most migrants in the cities they migrate to. This exclusion adds to the already vulnerable circumstances of migrants, who are living in congested rented rooms or slums with limited access to water, sanitation or health facilities. Since they have no local documents, they are not given access to public services, including ration shops, urban health centres, and housing schemes. Even their right to vote in the cities where they work is limited.

Beyond the loopholes, the very nature of gig work presents a host of problems. Based on a platform rather than factory or office work, it is highly individualised. Workers do not all have a shared space, so it is more challenging to create the kind of common solidarity or collective action. The implementation of ratings and user feedback instils an atmosphere of perpetual monitoring and competition. Workers are rated against one another, so any one low rating can impact their availability for future jobs. For migrants, who may struggle with language and digital literacy, it adds another layer of uncertainty.

Pie chart showing the skill composition of gig workers in India.

Source: NITI Aayog, India’s Booming Gig and Platform Economy (2022)

The gender factor also significantly influences migrants’ experiences in the gig economy. Most gig workers in India are men, but the number of women, particularly on urban service platforms like Urban Company, is increasing. For women migrants, gig work provides flexibility, but at the same time exposes them to harassment, wage discrepancies and a lack of security. App-based domestic services are a preferred workplace for many women, as they enable them to juggle childcare and household management. However, they frequently also report being underpaid, overworked, and lacking access to workplace protections. The inequalities appear to be wide, and there is a pressing need for a feminist perspective that deals with gig work.

Pie chart illustrating the sectoral distribution of gig workers in Tamil Nadu.

Source: The Hindu (2024), market trend analysis.

There are lessons for nations everywhere around the world. Spain’s 2021 Riders Law recategorised delivery workers as employees, entitling them to minimum wages and social security. In the United Kingdom, the Supreme Court ruled that Uber drivers should be treated as “workers” and entitled to fundamental rights, including paid holidays and the minimum wage. California’s experiment in reclassifying gig workers under the AB5 law was abandoned after Proposition 22 passed, despite intense lobbying by platform companies. These overseas examples demonstrate that policy change is possible if there are no barriers in place from influential corporate actors to block it. The problem is exacerbated in India, where labour rights are already enforced unevenly. Migrant gig workers fall between the cracks of labour law, urban governance, and welfare policy.

There is a need for some integration at this remote moment in time. Clear legal standards are needed to determine who gig workers are and what protections they deserve. Current labour laws need to be adjusted to ensure that this new way of working does not come at the cost of fundamental rights. Health insurance, accident insurance, and pension plans should be made portable, allowing workers to take their entitlements from one platform or city to another, with algorithmic transparency on platforms. Companies need to be held accountable for the transparency of their algorithms. Workers deserve to know how their pay is calculated, why their accounts are suspended, and how companies are rating them. Digital platforms need to have accessible grievance redressal systems. Urban thinking needs to change, too. Migrants must be recognised as an integral part of the urban realities in which they live and work. They should not be denied access to basic services just because their documents are from another state. Simplifying access to the public distribution system, health services, and voter registration would go a long way in restoring dignity and inclusion.

Workers’ organisation is equally important. Migrant gig workers are starting to organise through informal networks, unions, and digital platforms. Organisations such as IFAT, the Indian Federation of App-Based Transport Workers, are also lobbying for dignity at work and the legal recognition of workers. However, these groups are often unable to bargain collectively under current labour laws. Encouraging cooperatives, or platforms owned by workers themselves, could be a step toward greater self-reliance for gig workers and increased bargaining power. Digital literacy programs and legal aid centres oriented towards gig workers could also boost their capacity to navigate and fight back against extractive systems.

Migration is more than a demographic phenomenon; it’s also a journey of metamorphosis, aspiration, and accommodation. For India’s internal migrants, especially those employed in the gig economy, the journey is very often one of exclusion and deprivation. However, such resilience, adaptive capacity, and contributions to the urban economy go largely unrecognised. They figuratively hop around unfamiliar cities, learn new technologies, and work around the clock to send money home to those left behind. They are at the centre of India’s digital economy but on the periphery of its policies. That’s what needs to change now.

As India progresses toward a digital-first economy, the rights of its most vulnerable workers must be front and centre in that vision. The future of migration shouldn’t mean invisibility, and technology doesn’t have to come at the expense of fairness. Ensuring decent work for gig workers is not just a labour issue—it is a question of justice, equity, and the kind of society we want to build. The pandemic has already shown us the essential nature of delivery workers, cleaners, transporters, and domestic gig workers. Now it is time to acknowledge their contributions not only with applause but with rights, protections, and dignity.

Only when our policies reflect the realities of our most mobile, most vulnerable, and most indispensable workers will we build a truly inclusive economy. Migration will continue, as it always has, but the goal should be to ensure that it leads not to marginalisation, but to empowerment. The challenge for policymakers, civil society, and platforms alike is to rethink gig work not as a stopgap or a hustle, but as labour deserving of full rights and human dignity. In doing so, we not only strengthen our labour market but also honour the spirit of resilience that defines India’s migrant workforce.

References

Berg, J., Furrer, M., Harmon, E., Rani, U., & Silberman, M. S. (2018). Digital labour platforms and the future of work: Towards decent work in the online world. International Labour Office. https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_645337/lang–en/index.htm

BBC News. (2021, February 19). Uber drivers are workers, not self-employed, Supreme Court rules. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-56123668

De Stefano, V. (2016). The rise of the “just-in-time workforce”: On-demand work, crowdwork and labour protection in the gig economy. Comparative Labor Law & Policy Journal, 37(3), 471–504.

Friedman, G. (2014). Workers without employers: Shadow corporations and the rise of the gig economy. Review of Keynesian Economics, 2(2), 171–188.

Indian Federation of App-Based Transport Workers (IFAT). (n.d.). https://www.ifat.org.in

International Labour Organization. (2021). World employment and social outlook: The role of digital labour platforms in transforming work. https://www.ilo.org/global/research/global-reports/weso/2021/lang–en/index.htm

International Labour Organization. (2023). Social protection for gig workers: Emerging trends and policy recommendations. https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/non-standard-employment/publications

Kellogg, K. C., Valentine, M. A., & Christin, A. (2020). Algorithms at work: The new contested terrain of control. Academy of Management Annals, 14(1), 366–410.

Srnicek, N. (2017). Platform capitalism. Polity Press.

The Hindu. (2023, June 12). Delivery workers protest for better wages and conditions. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/delivery-workers-protest-wages

Van Doorn, N. (2020). Stepping stone or dead end? The ambiguities of platform-mediated domestic work under conditions of austerity. Comparative European Politics, 18(4), 637–655.

Wood, A. J., Graham, M., Lehdonvirta, V., & Hjorth, I. (2019). Good gig, bad gig: Autonomy and algorithmic control in the global gig economy. Work, Employment and Society, 33(1), 56–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017018785616

Government of India. (2020). The Code on Social Security, 2020. Ministry of Labour and Employment. https://labour.gov.in/code-on-social-security-2020

Leave a Reply